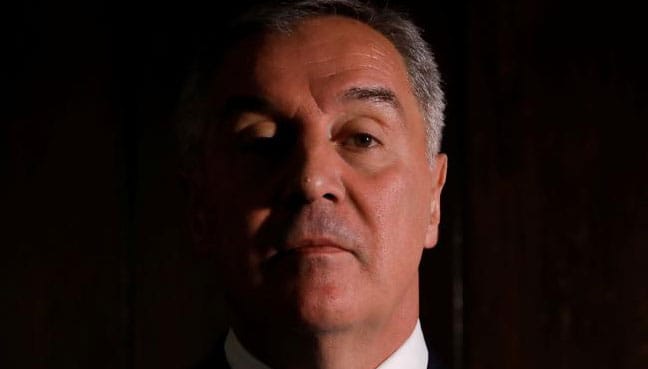

Milo Đukanović is the candidate of the ruling Democratic Party of Socialists and polls put him ahead of the opposition bloc’s Mladen Bojanić, a businessman who favors closer ties with Russia and Serbia.

The former Yugoslav republic joined the military alliance last year and hopes to join the European Union in 2025 at the same time as Serbia, though it must first reform the rule of law and eradicate corruption, nepotism, and red tape.

In other signs of strains with Moscow, Montenegro last month expelled a Russian diplomat over the poisoning of a former Russian double agent that the British government has blamed on Moscow. The Kremlin then expelled a Montenegrin diplomat.

Montenegro also joined EU sanctions against Russia in 2014 over its annexation of Ukraine’s Crimea peninsula.

On Thursday Đukanović said Montenegro was involved in a struggle between great powers.

“Disturbed relations between Moscow and Podgorica are a reflection of disturbed relations on the international stage … we hope these relations will recover,” he said. “Montenegro is … ready to accept every initiative that would lead to the recovery of bilateral relations between us and other countries.”

In 2016, the Kremlin wanted to “send a message to Europe and America” that NATO enlargement to the Balkans would intrude on its sphere of interests, said the 56-year-old.

On Wednesday, Putin told Montenegro’s new ambassador to Russia that the Kremlin was in favor of developing relations with the country.

Đukanović said the remarks were encouraging. “It would be important to see what deeds will follow such an assessment,” he said.

Đukanović is a former communist who rose to prominence in the late 1980s before the collapse of Yugoslavia in 1991. He led Montenegro, a country of 620,000, during the Yugoslav Wars in the early 1990s, oversaw a split with its former federal partner Serbia in 2006, and allowed the country tto gain NATO membership.

He denies opposition accusations that he fosters cronyism and corruption. Đukanović served six terms as prime minister and one as president with three brief interruptions.

“(Victory) is more important for Montenegro and its path than to me personally, I am someone who has fulfilled my ambitions in politics,” he said at his party’s office in the capital Podgorica.

He said he was confident of winning and that his defeat would give anti-Western opposition parties an opportunity to question NATO membership and would also slow the EU membership bid.

Montenegrin prosecutors say a group of Serbians and Russians plotted to kill Đukanović during a coup attempt at the 2016 election to prevent Montenegro from joining NATO. The Kremlin dismissed such allegations as absurd.

After the vote, he stepped down as prime minister, naming his close ally Duško Marković to the post. Đukanović remained at the helm of the ruling party and last month said he would run for president again, citing “responsibility towards Montenegro’s future.”

A survey by the Podgorica-based Centre for Democratic Transition in late March gave Đukanović 50.6% and Bojanić 35.5%. Other candidates were in single digits.