In the letter, Q humorously described an incident in which a tiger killed five sheep belonging to a European resident. And how on the following day, two tigers came and mauled four more sheep.

Q said despite having five armed men guarding the entrance of the home in anticipation of the big cat’s return, the men however froze instead of killing them as they sauntered in.

Q jokingly went on to say that the five men ought to be held responsible.

Who would have thought such an innocuous, humorous letter would lead to the closure of the oldest English newspaper in 19th century colonial Malaya.

The censors at that time took offence to the letter as it made comments about private persons, although not named, but which was considered to be in bad taste and frowned upon at that time.

The constant demands of the censor and lack of support from the authorities eventually frustrated the owner-editor of the Gazette to the point that he shut the paper down in July 1827.

However, the Gazette in its initial 21-year run, remains the oldest English newspaper to be ever published in Malaya to date, beating the Straits Times that came later in 1845.

‘Sold only 50 copies a month’

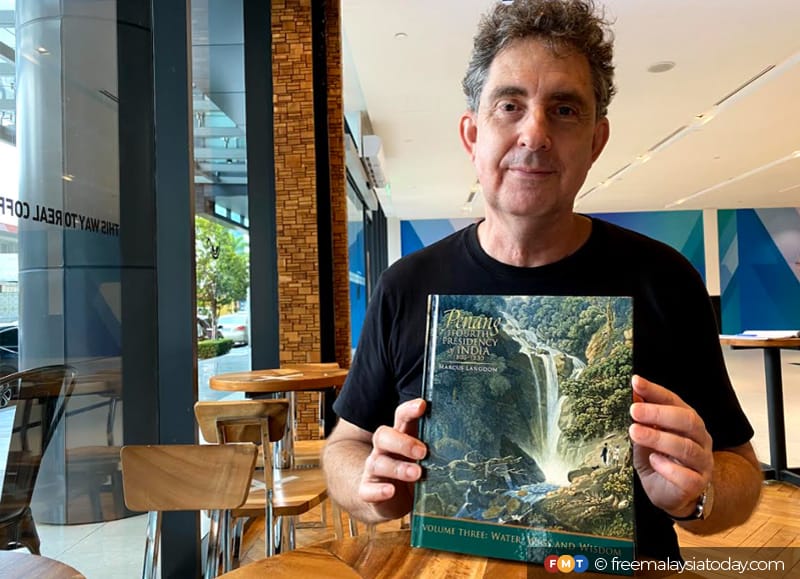

The story of the newspaper remains a colourful one, says Penang historian Marcus Langdon, who chronicled the history of the early newspapers of Penang in a new book.

The Gazette was published on Saturdays or in “extraordinary” editions, and was only available via a quarterly subscription of 7 Spanish dollars. It is likely that the Gazette had a circulation of just around 50 copies a month.

It primarily served the small European community and those who worked with the East India Company which held the residency of Penang island at the time.

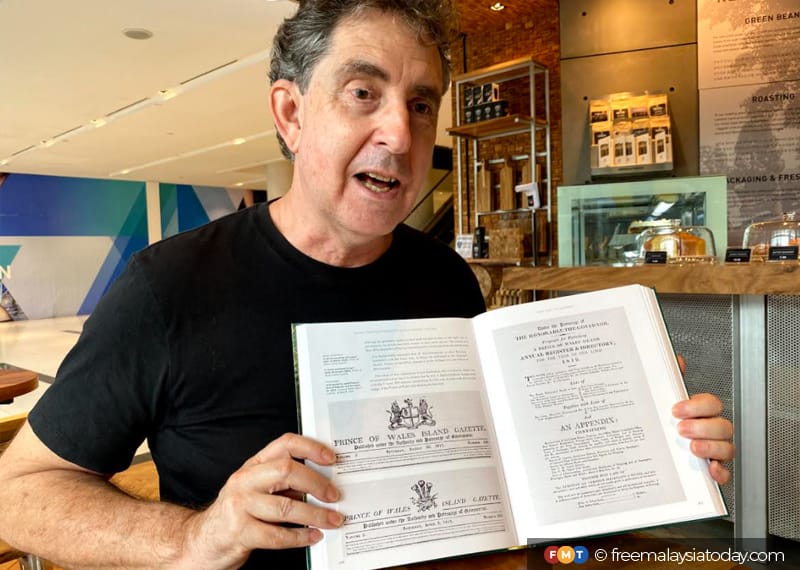

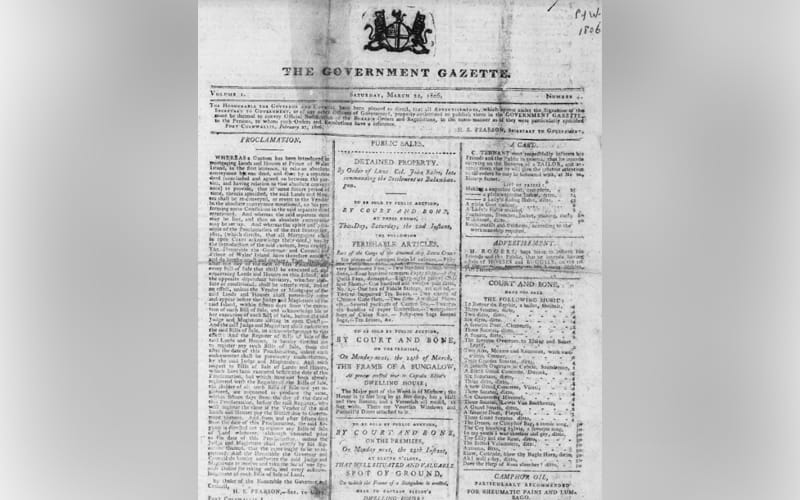

The Gazette’s inaugural edition was published on March 1, 1806 (but only copies dating from March 22 exist today) and consisted of four pages folded out of one sheet. The newspaper was first called the Government Gazette, but was renamed the Prince of Wales Island Gazette three months later.

It bore a masthead featuring the East India Company crest accompanied with the words “published under the authority and patronage of government”. The paper’s readers were merchants and the European population was about a hundred, at the time, Langdon’s extensive research showed.

‘Ran stories from other papers which were at least four to five months old’

On its front pages, the Gazette advertised items for sale at the port ranging from raspberry jams to precious china, and items for auction, primarily from Court and Bone.

Court and Bone got prominence on the front page as the newspaper was run by one of its partners, Andrew Burchett Bone, an Indian-born Englishman who had experience running two newspapers in Madras, The Hircurrah and the Madras Gazette.

Besides merchant ads, the Gazette also published stories from other newspapers in England, which were at least four to five months old, at a time when there was no telegraph in existence and the only information was passed through old newspapers that arrived on ships from Europe and from correspondence.

In return for allocations of about 100 Spanish dollars a month from the governor, the government placed official notices and newly drafted laws in the Gazette from time to time.

“One factor adding to the lack of public subscription support was that copies would be passed around among friends,” Langdon said.

The newspaper was printed in Beach and Bishop streets using old wooden printing presses in its early years, and eventually being printed at Bone’s home at Battery Lane, now a part of Jalan Sultan Ahmad Shah (Northam Road) between the old Protestant cemetery and the car showrooms.

After Bone’s death in 1815, the paper was run by BC Henderson until William Cox, the Penang Free School’s first headmaster, took it over in 1817.

‘Five-dot censorship riled up authority’

Langdon said Cox quit the business in 1827, following pressure from the censors and also after the government withdrew patronage via its monthly allocation.

One of the last editions of the Gazette was printed with a heavy border, similarly used for obituaries, in trying to denote its impending demise.

After the Gazette came The Penang Register and Miscellany, started by Norman McIntyre and William Balhetchet which was in circulation for about a year until 1828 when it was shut down by the government after it ran afoul of the strict censorship regulations.

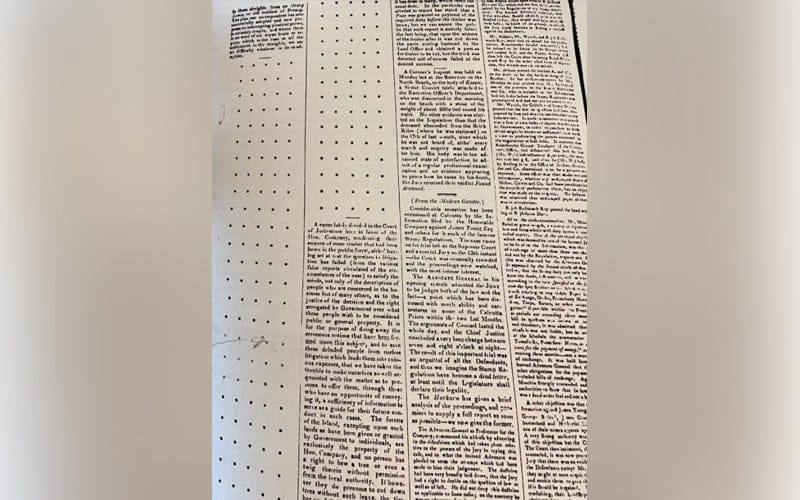

The paper inserted five black dots on columns that were censored, by doing so it embarrassed the government and was forced to shut down.

Langdon said the East India Company then decided that they would print their own newspaper, the Government Gazette, with printing presses shipped from Calcutta. But this paper too ceased publication when the Penang Presidency was abolished in June 1830.

Cox then returned to print the Gazette in 1833, which lasted three years until his death in 1836.

“The impact of censorship on the pre-1830s newspapers was apparent, judging from the limited social comment found in these papers.

“Any slightly controversial content would be cause for non-acceptance by the authorities. One can also see the impact the personality of each governor had on news content then.

“Governor WE Phillips was more genial than the somewhat severe Robert Fullerton.

“The several strongly independent-minded newspaper owners and editors in Penang, Malacca and Singapore certainly played their part in finally achieving a level of press freedom three years after the end of the Presidency,” Langdon said.

Later, the Pinang Gazette and Straits Chronicle printed its first edition on April 7, 1838, and was run by a consortium of local European merchants headed by James Fairlie Carnegy.

It was eventually sold to a newer publisher, Penang Echo, which was, in turn, sold to The Straits Times.

In the years to come, many other newspapers would come and go, such as The Pinang Argus (1867-1873), Straits Echo (1903 to 1986) and at least two dozen others set up in Penang.

Langdon’s new book Water, Wigs and Wisdom in the series Penang: The Fourth Presidency of India 1805-1830, will be available from June 1.